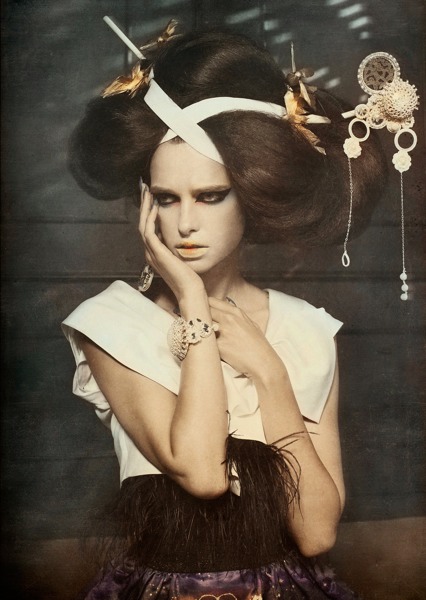

'Hanjo' by Yoram Roth

Arts & Events, People - by Cathy Marshall

German fine art photographer Yoram Roth is a man of many talents. From set construction and garment creation to floral arranging, Yoram is involved with almost every detail involved in the production of his highly considered images. By utilising techniques generally used within commercial imagery, Yoram sells narrative over product. He plays with the familiar language of fashion photography to lure the viewer into an open state, ready to receive a narrative.

His most recent project, Hanjo, speaks of the courage of committing to true love. A step in a fresh direction given that many of his previous images are highly sexualised. In Roth’s words, Hanjo is “like living sculpture”. The story is based upon a 15th Century Nôh Play (Japanese opera) and has come together in photo book form, which Roth explains is the ideal medium for photography.

On the eve of his visit to Tokyo Photo and the release of Hanjo, Yoram talks to Cathy Marshall about Hanjo, how to perfect a project, and recently being picked up by Camera Work in Berlin.

Your work is incredibly controlled and meticulously executed; do you have a background in commercial photography?

I have never shot anything commercially. I really went to great lengths to acquire the skills and style to shoot this way, but it was clear to me that I did not want to pursue an actual career in commercial photography. I believe a lot of people really underestimate the effort it takes to become a fashion photographer.

I think it is “easy” to create pretty pictures in nearly any fashion style. It will take some accumulated experience and a healthy budget, but anyone can learn to shoot well. Not to sound snarky, but there are thousands of fashion photographers on PhotoVogue right now, with some great images.

I studied with certain photographers. Melissa Rodwell was one of my teachers, and she is now actually part of the team that is launching BREED, an online school for high-end commercial and fashion photography. That’s a great group of people to learn from. What people misunderstand is the entire universe beyond image creation. As a commercial photographer you really need to run a business. You have to be able to execute consistently, on time, and on budget. Conversely as an artist, you need to be very deliberate about the creative choices you make. Sure, plenty of people are willing to buy a nice-looking print and hang it on their wall; that’s not art, that’s decoration. Art requires more. And as an artist, you need to communicate your creative intent. You also need to get out there and show it to galleries, at fairs, and to collectors.

A large number of young photographers get very mad when I say this, but I really don’t believe it’s possible to start two careers simultaneously. Either be a commercial photographer, or a photographic artist. You can’t do both, they’re very distinct lives, and it takes years to get any traction. Yes, you create strong images, but that’s pretty much all they have in common. I can think of a number of names who sort of do both, but that’s not how they started. Whether it is Erwin Olaf, Gregory Crewdson, or Izima Kauro, they each come from a specific creative place. Also… things are different now. Not to sound my age, but when we were still shooting film there was a LOT fewer photographers out there.

Not to mention that each industry is wary of the other. The art world wants to work with committed artists when dealing with photographers who are emerging, not someone who is dabbling on the side. There are plenty of talented creative people, but talent is not enough. The galleries want to know that an artist is fully committed if they in turn commit their limited resources. The same holds true for a commercial agency. The photographer should not be a neophyte with a unique vision; the agent needs to rely on this person to execute an important part of someone’s campaign. A good agency will expend substantial time and energy building up a commercial career.

How does the stylistic reference to fashion photography enhance the stories within your work?

Modern people see thousands of images every day. On websites, in magazines, and selling us products and services from every conceivable surface… walls, buses, high-rises, billboards. There are marvellously beautiful, perfectly cast people smiling down at us. The images let us know that if we buy these products – if we use these services – if we take that trip – we will be better. Not quite as good as those incredible people in the advertisement, but better. They promise us that others will find us more attractive, or that we will be safer, or more respected by the community.

That wasn’t always the case. Until very recently, people only saw images occasionally. Go back four or five long generations, and people saw maybe one or two images a day… and before that, it would be a painting at a rich man’s house, or something dramatic in church. Those paintings served the same purpose… though they were selling a slightly different product. They would illustrate stories from the bible for the illiterate public, but the images also did something beyond being narrative. They let the beholder know that if they were pious, it would make them better. Not quite as good as the saints, but it would make them more attractive in the eyes of God, it would make them safer, it would make them respectable.

People have developed image filters. We had to over the last forty years. When dealing with so many images every day, we have learned to look and promptly dismiss what we’re being shown. We look, and instantly understand we’re supposed to use a certain body spray, buy a car, go on an adventure, or simply smell like we might. We filter them out of our conscience.

But it is exactly at this point where I find creative opportunity. By using the language of commercial and fashion photography… Showing beautiful models, well-cast character actors, agile dancers, all placed inside narrative images, I breach the viewer’s image filter. The viewer recognises the familiar language… but nothing is being sold; the filter breaks down. It is unclear what is being pitched, what the product is… and that is where I try to tell stories, to engage the mind that back-fills the missing narrative.

Hanjo was conceptualised as a printed publication. How important is the book as an object to you?

Extremely. I consider the photo book to be the ideal medium for photography. The viewing distance is perfect, as is the way it fills the field-of-view. But more importantly, you can spend as much or as little time with an image as you like. In a gallery you’re often forced to move along, or worse – expected to stand there when you really want to walk away.

You are very interested in the notion of the story. Your work references German children’s stories, Edward Hopper paintings and Japanese plays. Does this make creating a series of work important, in which to take the viewer on an equivalent journey?

I prefer images that invite a narrative, and I work in series. Sometimes I tell a story, and other times I leave room for the viewer to figure things out. However I have done work that relies simply on visual context. I shot an homage to Christo & Jean-Claude’s early work, and that was simply image-driven.

A set built within Yoram’s Berlin studio (Pic: yoramroth.com)

A set built within Yoram’s Berlin studio (Pic: yoramroth.com)

The sets for your most recent body of work ‘Hanjo’ are even more elaborate then those constructed for your older series. They include not only the backgrounds and set itself, but traditional clothing, paintings, tapestries, floral arrangements etc. How much time goes into pre-production, compared to shooting and post?

Hanjo was 80% pre-production. I created an eighty page document with endless mood boards, sketches, quotes, ideas, etc. I spent about nine months going into deep geek-out mode on all things Floating World. I went into this total obsession with all things Japanese. I even went there, and bought all kinds of fans, fabrics, and other little props.

Ultimately I shot it in three days, with a team of eight people. Hanjo was more like a movie production in that I had a complete shot list of about seventy images in ten distinct scenes that I needed to capture. It’s the last time I shoot like that. I made it work, but it really leaves no room for creative experimentation. There’s one scene that I wanted to play with some more… but I couldn’t make the light work the way I wanted, and I was running out of time. So I had to skip my idea. But it’s a really efficient use of resources, there’s a reason films get shot with a script and a shooting schedule.

‘Hanjo’ is an homage to Yukio Mishima’s version of the 15th Century Nôh play, (think opera). Were your images based directly from stills from the play or were they from your mind, inspired by the play?

They are completely new. A traditional Nôh performance is actually more like living sculpture. There are very specific poses with masks that the performer needs to hold while reciting the lines. Hanjo is really a bunch of ideas all tossed together. I really love those hand-colored images from Japan that were created in the 1860s right up to the turn of that century. They’re beautiful. But I also went through this phase of reading every graphic novel I could find, spending all my time at Forbidden Planet in New York or Golden Apple down on Melrose in LA. I still think this is an incredibly powerful medium for telling a story, and I am surprised more photographers aren’t creating hybrid forms like this. My Hanjo isn’t a photographic comic book, it’s really more of a dream sequence – but that fits in this case, so much of Nôh is otherworldly anyway.

Your images are often highly sexualized, such as the Hopper’s Americans: Stories From Sun-Lit Rooms series. Is this something you adhere to for a particular reason?

Good heavens, wait till you see what I am currently working on… I expect to be banned from certain countries. Yeah, sexuality matters. But I’m still formulating my take on that, so it will have to wait another year until I explain it further.

Reading and Waiting, Long Into the Night. Taken from the series Hoppers Americans: Stories from Sun-Lit Rooms

Reading and Waiting, Long Into the Night. Taken from the series Hoppers Americans: Stories from Sun-Lit Rooms

You have recently been picked up by Camera Work in Berlin who also represents the likes of Stephen Klein and Nadav Kander. Do you feel this representation has solidified you as a contemporary photographer in Germany?

Very much. Working with CAMERA WORK means I have time. Everything changed. For several years I was shooting various projects as quickly as possible in an effort to realise my visions, because I wanted to create a body of work that I could point to. Now suddenly the mission is the opposite. Go slow. Focus on perfecting a project. It’s become a very different creative process. I’ve been shooting a single project for over a year now, and it affords me considerable creative luxury. My gallery has told me repeatedly that they’re happy to put on a show, with one caveat: I need to feel that it’s ready. They are very committed to building their emerging artists, and they realise it takes many years. CAMERA WORK has an incredible roster of artists, and living up to my place amongst them really means not showing new work until it’s ready.

Yoram appears representing Camera Work at Tokyo Photo, September 27-30. The limited edition release of Hanjo is through Camera Work.

Yoram Roth

www.yoramroth.com

y Yoram Roth (Pic: Ivanto Scanelli)

Yoram Roth (Pic: Ivanto Scanelli)

By Cathy Marshall

Photographer

www.cargocollective.com/cathymarshall