-

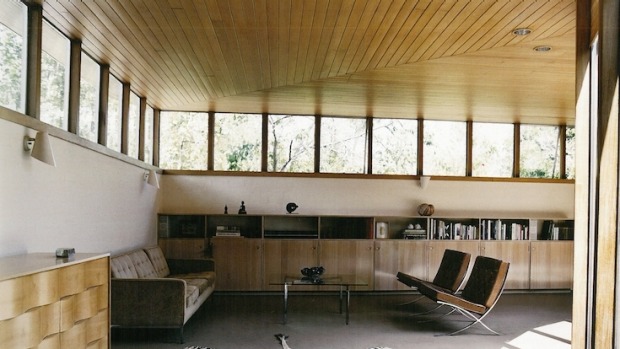

Grounds House

“He Makes Houses Reflect Our Lives” by Colin Fraser first appeared in The Australian Home Beautiful in July 1949. Recently revisited in the Robin Boyd Foundation‘s Influential Apartments Open Day, the article is a unique glimpse into Australia’s architectural ‘Golden Age.’

The work of Roy Grounds, architect, lecturer at the University of Melbourne, and one-time set designer for M.G.M., usually provokes vigorous argument among Australian architects and among interested laymen. In this interview he discusses his approach to the design and construction of buildings to suit Australian conditions.

A proportion of architects greet Roy Grounds’ name with something like righteous horror. Some claim that his introduction of “modernist” designs in the ‘thirties has lowered the Australian standard of solidarity and dignity. Others, like research man Robin Boyd, say he is the best since Burley Griffin; a few say he is a genius.

Of the doubters: Their main complaint seems to be that the flat roofs which he popularised in Melbourne, and such innovations as the use of painted brickwork for inside walls, have broken with Australia traditions for no better purpose than to be different.

But his admirers say that Grounds’ buildings, whether blocks of flats or domestic structures- many are on challenging sites- are notable for their clean functional simplicity, for their sensitive use of native materials and for a straightforward economy which increases rather than detracts from their appearance.

They say they give the impression of a free mind at work. Each building has a central theme which is followed to the smallest details; the whole creating a harmonious composition pleasing both to the spectator and the occupier.

They say, too, that if there is a truly Australian architecture, developing, this is it.

Quamby Flats, Roy Grounds, 1941-42. Photo: Rory Hyde,

Grounds, who is, naturally enough, on the side of Grounds, admits that his buildings are different.

“They are different purely because I am not interest in being different,” he says. “They are obvious in the most obvious ways- and they happen to be different because nobody will do the obvious.

“It amazes me that they are different, when they are finished. I wonder by what contortions and confusions of thought people can possibly produce the buildings they do.

“Too many buildings show a lack of clear thinking, a lack of modelling, a failure to appreciate materials for their simple worth; failure, perhaps, to understand our background, climate, and labor conditions/

“Architecture to me grows out of living a full life and of understanding life and human beings. Any building which is a creative building is a personal expression of a point of view.

“Domestic architecture, as distinct from commercial architecture (buildings on a vast scale impersonal in their character) is essentially a portrait.

“It is an outward expression through the eyes of the artists (in this case the architect) of the personality, character and background of the individual responsible for the building project- the owner-occupant.

“When a domestic structure becomes that, it ceases to be part of the science of building; it becomes the art of architecture.

“It is the difference between a street photographer’s snapshot and a portrait by Dobell.

“I have never used a new material. I have used materials which other people have abused.

“I am sympathetic to materials. I will ease the, I will encourage them. I won’t use a club on them.

“If it is stone, it will look like stone. Wood won’t be made to look like anything but wood. Each material is treated according to its special qualities.

“There is nothing new in this. It is only the acceptance of principles established for 3000 years.

“We lost decent principles in the Victorian and early Edwardian eras. We are just going back to the basic principles. Contemporary architecture is no more contemporary than the great buildings of Athens 2000 years ago. They were contemporary then, and any really contemporary work today will be the subject of history 100 years hence.

“But it has to be truly contemporary, without affectation or obviously striving for effect.

“There are no bad clients. The only excuse for a bad building is a bad architect.”

Moonbria

At 43, Grounds is what some people might call eccentric. Archimedes-like, he has been known to call a client excitedly in the middle of the night if he happened then on the solution to a problem.

He refuses to provide clients with “pretty elevations complete with beautiful trees” until that last detailed drawing has left the draughtsman’s board. The client is welcome to spend all day with him as the drawing progresses, asking for alterations, but- no pictures.

The house must grow up, says Grounds, not be squeezed and pounded to conform to a per-conceived idea.

Every solution, he says, is entirely new. It fits one site, one person, one problem. There is no formula except sympathy and understanding of the site and the problem. But each solution bears the impress of the architect’s personality and approach.

He adds: “To design you must take the broad open viewpoint. You must approach each problem as though you have never faced such a problem before in your life. You have no idea what you are going to do; nothing except supreme confidence in your ability to do it.

“The conception of a building demands terrific concentration and no drawing

“It is an exhausting process when it is finally conceived- and nothing can stop it from being right.

“The building must be conceived as a whole and in comprehensive detail, without reference to documents or the need to put things on paper.

“It is conceived with one essential, main driving force. One idea, one question, which goes through all parts of the building to the smallest detail. There is no need separately to design any of the detail. The details are all part of the whole, and they are the whole.

“One column which is right for one building will not be right for another. To copy a well-liked window from one building to another is as incongruous as to say. ‘That is a beautiful nose. We will put it on this girl’s face.’”

Grounds believes that sounds Australian architecture should reflect certain national qualities, qualities which he says he came to appreciate not so much by looking at Australian as by studying the habits and living conditions of people in other parts of the world.

The truly Australian characteristics, he says, are generosity, an open mind, lack of the restrictions of a fixed tradition, an innate feeling of limitless space, end-less opportunity, enthusiasm.

Roy Grounds for the Small Homes Service

It is not hard to find these in his house in Moralla Road, Malvern; in Clendon Flats, and Clendon Corner, Toorak; in his block of Boulevard flats overlooking the Yarra; in his own home, “Ranelagh,” at Mt Eliza; and in the newly completed home of Lady Rutherford in Barwon Heads.

But besides conceiving his buildings in satisfying outward shapes, Grounds regularly pleases the occupiers by providing them with maximum comfort at minimum inconvenience.

To do this he undertakes, with almost diabolical cunning, a series of searching investigations into the character and habits of his clients.

An interview goes something like this:-

The client rings up and makes an appointment

“I would like you to design me a house,” he says when he arrives.

Grounds: Why?

The client: We need a house to live in.

But why me?- I have heard about you. I liked one of your buildings. Mr Smith told me about you.

Very well. Have you a site?- Yes or no.

How many in your family?

What do you do for a living?

What do you do at night?

Do you and your wife share a bedroom?

Your children?

What are you daily habits?

At about this stage, the client usually breaks in with: “There’s a house in such-and-such street which my wife and I admire-“

Grounds: Mr Smith lives in that house which you admire. Our problem is to build a house to suit YOU. Let’s talk about you.

In an hour, Ground claims, a student of human nature can find out a lot about a man. But not enough.

Before the client leaves, he finds out where he lives. He finds out where he lives. He finds out, in some detail too, how the client and his wife entertain (how they SAY they entertain), and such things as whether the cupboards are clean or dirty.

Several days later he may drop in casually at their home at a time when he knows they are both home.

“They don’t know I’m coming, and I find out exactly how they DO live,” he says.

“They may have felt obliged to ask for big windows and plenty of sunlight. When I get there I find that the curtains are drawn. They really don’t want the sun.

“Later I make an appointment to see them in their house when they do expect me.

“After that visit, I start to get an idea of just what they are like. All that is required then is to sum up the three conditions, making common-sense allowances, and express the result.”

The result should be a house reflecting their personalities and needs, combines with the imaginative foresight of the architect.