The Burnout Generation

Ideas - by Open Journal

Hugh Simpson was in his final year of studying architecture at Melbourne’s RMIT University when he realised something was wrong with his health.

“I thought it was cancer,” he says.

But a trip to the doctor delivered unexpected results. It wasn’t cancer Simpson was suffering. It was anxiety.

Looking back, it’s unsurprising Simpson, 27, was feeling anxious. He was studying 18 hours a day, seven days a week, determined to do well in his degree so he could land a good job when he graduated.

“It was hellish,” says Simpson of the unrelenting pressure he felt to achieve while at uni. “There were times when you wanted to kill yourself.”

Simpson’s story is not unique. According to the 2015 Future Leaders Index commissioned by university campus retailer Co-op and accountancy firm BDO, 49 per cent of 18 to 29-year-olds report feeling stressed all or much of the time. And results from the Australian Psychological Society’s Stress and Wellbeing in Australia Survey 2015 reveal young adults continue to report higher levels of stress and distress than older Australians.

It comes as no shock to Simpson that so many of his generation are living with some level of psychological distress. He reveals he has lived with four people who “suffered complete mental breakdowns”, all around the time they were finishing their thesis or major uni project.

“I have seen people completely change from happy-go-lucky to, when the pressure is put on them to succeed and to achieve, they have lost it,” he says. “They have absolutely lost it.”

When 28-year-old Jerome Doraisamy from Sydney was balancing his demanding law degree with working as a paralegal and fulfilling various volunteering commitments, he suffered “a mental breakdown” in 2011.

“Having that kind of workload consistently for two years and surviving on four to five hours’ sleep a night was pretty draining,” he says. “And, ultimately, it was something I wasn’t able to maintain.”

Now successfully managing his mental health, last year Doraisamy released The Wellness Doctrines, a “survival guide” for young law students and legal professionals to manage their health and wellbeing. It features personal stories, first-hand accounts and case studies of more than 45 legal professionals and health experts, as well as practical strategies Doraisamy implemented during his recovery. By encouraging these young people to take control of their health and wellbeing, Doraisamy hopes others won’t have to go through what he did.

And it seems The Wellness Doctrines is already making its mark. Since its launch in September it has sold copies across six continents and reached number two in the Body, Mind & Spirit category on iTunes.

So what is fuelling high rates of stress and distress among young Australians such as Doraisamy and Simpson?

Former federal political adviser Jennifer Rayner believes financial pressure brought on by tough job and housing markets is partly to blame. Rayner’s so passionate about the struggles of her generation, she has penned a Redback Quarterly essay on the topic: Generation Less: How Australia is Cheating the Young.

In it, she says, “I see my generation becoming the first in more than 80 years to go backwards in work, wealth and wellbeing.

“I find people in their 20s living out an ever-extending adolescence as the building blocks for a stable, comfortable life slip further from their reach. I hear brittle laughter at black jokes about renting till 50 and retiring beyond the grave.”

Rayner points out while there have always been more young Australians struggling to get enough work than older ones, in the 1970s fewer than one in 30 young people were underemployed, compared to one in six today. Furthermore, the proportion of young people in casual work has jumped from 34 per cent in 1992 to 50 per cent today, with casual workers typically experiencing limited access to entitlements and an unpredictable income.

The tough job market was one of the reasons Simpson felt compelled to work so hard at uni. But, he says, he’s yet to enjoy the fruits of his labour.

“I thought when I was 23 I’d be done with uni and I’d get a good job. But it’s almost four years later and I’m only just now earning a living wage. That life goal or that point you’re supposed to hit at a certain age just keeps moving.

“Then there’s the fact that we’re priced out of the housing market. My parents told me, ‘At your age we had property,’ but it’s just not possible [nowadays] unless you choose really particular avenues. It’s hard.”

Housing unaffordability is young people’s number one concern according to the 2015 Future Leaders Index, followed by falling job opportunities, global warming and a declining economy.

Sydney-based social researcher Claire Madden agrees the current housing and job markets place significant pressure on young people. She also believes young people’s heavy use of technology, particularly social media, is negatively affecting their health and wellbeing.

“The times which we used to build into our day for reflection are now crammed with checking emails, watching YouTube videos, scrolling social media feeds or playing entertainment apps,” says Madden. “The result is we’re constantly switched on and feeling wired.”

Indeed, the Stress and Wellbeing in Australia Survey 2015 found almost one in three heavy users of social media – those connecting more than five times per day – find it difficult to sleep or relax when they disconnect. Just as many feel their brain “burn out” with the constant connectivity of social media. And no one’s feeling these effects more than people aged up to 35, who are four times as likely as older generations to be heavy users of social media.

Madden points out the more heavily young people are connected to social media, the more likely they are to experience “FoMO”, that is, a “fear of missing out” on an exciting or interesting event their friends or peers are involved in, often sparked by seeing a social media post.

“I think that because now we can see so much of everyone else’s world, we do have that feeling that we’ve always got to run to keep up and we’re comparing the behind–the-scenes version of our lives with the show reel of other people’s lives,” says Madden.

Dr Cindy Nour, a clinical psychologist from Sydney, says, “If you’re already a bit vulnerable to feeling low or anxious you can start to make comparisons where you think other people are having far more fun and cooler lives than you are. But to compare yourself to those photos on social media is quite a flawed comparison because people are not going to put a photo up of how they look when they wake up in the morning. They’re going to do what we call “positive impression management”.”

And it would seem many of us are being fooled by this positive impression management, with 46 per cent of 18 to 35-year-olds admitting they experience FoMO at least some of the time.

Rose Landau, a 31-year-old management consultant from Melbourne, sees FoMO as a real issue for her generation.

“The availability of media now means we’re exposed to so many different lifestyles and choices and each one is made to look so attractive,” she says. “I think it’s a huge part of the problem, a sense that no matter what I do it won’t be the right thing, there’s always something better, there’s always someone who seems to be optimising everything.

“We feel like we’ve failed because we haven’t got the amazing travel experience of one friend, plus the professional success of another, plus the cultural exposure of another.”

FoMO has become such a widespread issue that proponents of a minimalist lifestyle are joining the growing JoMO (joy of missing out) movement that promotes a more healthy relationship with technology. JoMO encourages people to unplug from technology more often in favour of “real-world” experiences, such as reading, exercising and getting out in nature.

Dr Nour says, while social media can be a fantastic way to make new connections, real life engagement is important and it can serve as a buffer to depression, anxiety and loneliness.

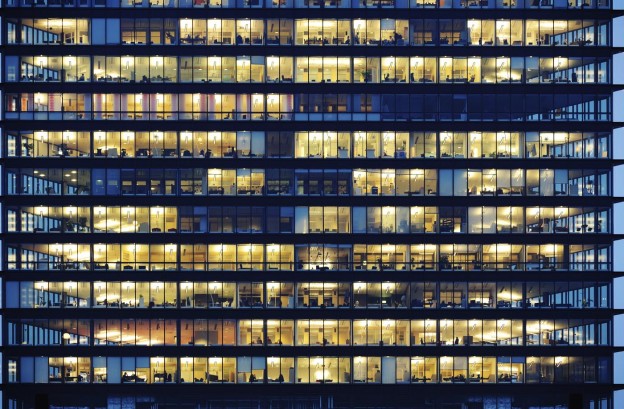

There’s no denying disconnecting from technology more often is good for our health and wellbeing, but what about the pressure many of us now feel to be constantly connected when it comes to our working lives?

“If I could state the single biggest impact to my weekends and my winding down, it’s my fucking work phone and my fucking work emails,” says Landau. “It’s absolutely relentless and there’s no sacred time.

“It’s gotten massively, massively more stressful and difficult to manage because of the connectivity and the emails on your phone and just being available and being online all the time.”

Landau estimates she spends up to 90 hours a week working, including time spent in the office and answering work-related emails and calls from home. This lack of work-life balance not only takes a toll on her physical and emotional health, it also affects her relationships.

“Because I’m an introvert I find it a lot harder to maintain friendships and relationships as so much of my weekend is dedicated to deliberately being by myself to try and recharge,” she says. “I need at least a solid 24 hours of just no one in order to be able to get back up on the Monday morning and do it all again.”

When it comes to romantic relationships, Simpson sometimes wonders how people manage to fit them in at all.

“I’m 27 and I’ve had two relationships in my life and I can’t see how I’d fit another one in,” he says.

The 2015 Future Leaders Index found 77 per cent of 18 to 29-year-olds’ personal and social lives suffer when life gets too busy. But, interestingly, 61 per cent feel stressed if they’re not busy.

Madden believes we’ve created a modern-day virtue of being busy, and that we think it signifies success and productivity. But she cautions being busy is not the same as achievement and we need to look at what we’re busy doing.

Landau sees a generation addicted to achieving and unwilling to waste even a second on anything that doesn’t contribute to their “life CV”.

Simpson would agree. He feels guilty if he spends even a night lounging around.

“You feel like you’ve wasted a night,” he says, “Like, you should be reading a design book or instruction manuals, studying another language or educating yourself in some form.”

Landau says, “Everyone has this relentless sense of markers of time passing. Have you done the travel? Have you achieved the professional success? Do you own your own home?

“Everything’s got to be worth something. I definitely think we all feel it [pressure] and I think we believe if we take our foot off the pedal even a tiny bit we’re losing or wasting time that we won’t be able to get back.

“I don’t think that any other generation has felt pulled in as many different directions as we have and that’s the flipside to opportunity. I think the expectations that we have placed on ourselves are broader and more unachievable than they ever have been before.”

Dr Nour says to successfully manage our health and wellbeing it’s important we drop these unrealistic expectations of ourselves and realise we’re only human.

“We’re not machines,” she says. “It’s like having an expectation that you could do long trips in your car on a very empty tank of petrol, without servicing the car or filling it up with high quality fuel.”

Doraisamy – the young lawyer who suffered a breakdown in 2011 – knows better than most the dangers of not prioritising health and wellbeing, and he too urges his generation to slow down.

“Now that I recognise health and wellbeing must be the number one priority, I feel I’m able to be much more efficient and productive across the board. I enjoy my days much more than I used to and that’s something everybody should be able to do.”

Words: Kate Jeremiah